![Jac Caglianone [608x342]](https://a.espncdn.com/photo/2024/0625/r1350390_608x342_16-9.jpg)

Brazil s Bia out of Olympics with stress fracture

Shohei Ohtani has taken MLB by storm and captured the imagination of fans by becoming a two-way sensation, excelling both at the plate and on the mound, and stretching the idea of what a player can do.

Seemingly every year, there are MLB draft prospects who likewise capture the attention of teams with their ability to both hit and pitch as prep and college stars. This summer's class is no different as two projected high first-round picks, Florida 1B/LHP Jac Caglianone and Mississippi high school SS/RHP Konnor Griffin, are good enough both ways to give teams a decision to make.

"If both of them had never touched a bat in their lives, they'd still go in the top 50 picks as pitchers," a scout told ESPN last week.

But remember, pitching and hitting at the professional level is hard. Even Babe Ruth was only a true two-way player for two seasons, and nobody other than Ohtani has come close to starring at both at the same time. Teams hesitate to commit to developing prospects who truly split their time in pro ball. The reality is that almost every player who enters the draft as a two-way player will become either a pitcher or position player well before reaching the majors.

Deciding which area to specialize in isn't easy when a player has seven-figure talent at two very different skills, but new tools have made it easier for teams to make the call, and while even the best two-way stars are unlikely to become "The Next Ohtani" in the majors, being able to excel both on the mound and at the plate adds value to a prospect's draft profile.

Here's an inside look at how the two-way-player decision plays out in MLB draft rooms through the cases of this year's most intriguing candidates.

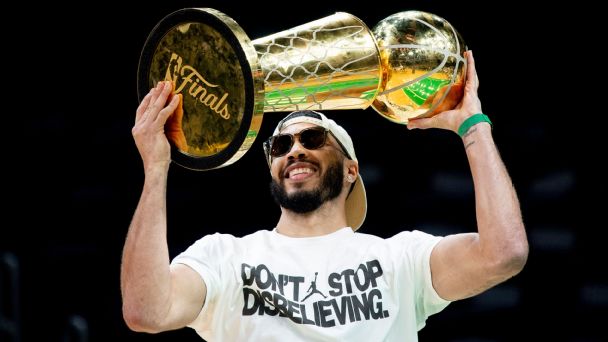

The prospectsJac Caglianone

Caglianone is the most famous college baseball player, earning the nickname Jactani for his two-way prowess in the nation's best conference. He has top-of-the-charts power with plus bat-to-ball ability at the plate, and throws up to 100 mph with the potential to become a true major league starter on the mound.

After drawing attention as a potential future No. 1 overall pick last season, Caglianone took his offensive game to another level this season -- and in the process made the two-way dilemma much clearer for teams interested in drafting him this month.

There are still two reasons he isn't the consensus top prospect in this draft as a hitter. First, his future home as a position player is either as a first baseman or corner outfielder, which makes him less desirable than a middle-of-the-diamond prospect to teams picking at the top of the draft. And second, his chase rate (percentage of swings at pitches outside the strike zone) is high enough that it has raised the eyebrows of many evaluators.

While Caglianone was crushing college pitching this year on paper -- posting a 1.419 OPS with 35 home runs with a strikeout rate that dropped from a solid 18% last season to a great 8% -- the fact that his chase rate hovered in the 37-40% range (compared with a national average of 23-25%) raises two key questions: Does he have to correct this to a real degree against better pitching in pro ball? (Likely.) And is his issue more ingrained than adjustable at the next level? (Nobody really knows.) It is rare for a strikeout rate to be cut in half with a very high chase rate, but that underlines how good Caglianone is at putting the bat on -- and sometimes hitting homers off -- pitches outside the strike zone.

There are two ways that teams could land here: The first is something similar to what I call the concrete plate discipline theory. The more reps a hitter gets against a high level of competition, the more his current level of pitch selection solidifies and simply becomes who he is at the plate.

The second theory is that pitch selection can be changed -- possibly to a big degree -- as long as the hitter shows a strong in-zone contact rate. The thinking goes that the hardest thing in baseball is seeing a pitch, identifying the type and location, deciding to swing, then swinging, and hitting the ball (preferably hard). If a hitter shows that he can do that well (i.e. a better-than-average in-zone contact rate), then choosing to lay off that slider off the plate is easy. It's easy because you'd do the first half of that sequence, then just do nothing else.

"Projecting him to improve his pitch selection really depends on understanding what he's thinking now," a scout said. "We've talked to players that have approaches that we'd never guess -- being told to never swing at this pitch, or always swing in this count -- so you have to start there and see if there's a small change that could make a big effect."

Later in that conversation, recently-promoted Nationals prospect James Wood came up as an example of a hitter that had swing-and-miss concerns in his draft year of 2021 (at IMG Academy in Florida). He corrected it almost immediately in the majors, and it was almost entirely due to a mental adjustment to his approach at the plate.

As a pitcher, Caglianone can look like a true first-round talent on the right day. Where he throws his slider proves he can throw the pitch over the plate, but he has some trouble hitting the best locations consistently. The Stuff+ of the pitch (an algorithmic score teams use to measure a pitch based on its movement profile from TrackMan data) is a bit worse (major league average, or a 50 on the 20-80 scale) than it looks to scouts in person (above average, maybe plus). In Caglianone's case, this could mean that the location and quality of the pitch could be improved, which might lead to him taking off as a pitcher.

On the mound, he's seen as a second or third-round prospect because of that triple-digit heater, his starting pitcher build, delivery and durability along with the ability to throw three average-or-better pitches for strikes. His offspeed stuff is more average to a bit above, maybe flashing plus on a good day, and his command and execution (i.e. hitting intended locations, rather than just throwing it over the plate) are just OK, particularly later in starts.

Konnor Griffin

While not nearly as well-known to fans as Caglianone, Griffin is also an electric athlete who has stood out to scouts since early in his high school career. He possesses a skillset that reminds me of Fernando Tatis Jr. and makes him a top-10 prospect in this draft.

He is 6-4, 205 pounds with 70-grade speed, 70-grade power potential, a 70-grade arm, and the tools to stick at shortstop -- but if that doesn't work, he could literally play any position on the field. The biggest drawback to his profile as a hitter: scouts question if his swing path will be conducive to pro ball.

But Griffin is ready to make an adjustment if his team asks him to.

"I'll adapt to the hitting system I'm in," he said. "Those coaches are in those spots for a reason, so I'll listen to them ... I've been working on staying tight and keeping my bat path through center field. Especially since the high school season is over, I'm able to tune things up in the cage."

Griffin is a second round-level prospect on the mound with mechanics and a scouting report that remind me of Detroit Tigers starter Jack Flaherty at the same age before he went in the first round of the 2014 draft. Given the way draft bonuses work for prep pitchers, Griffin is a $2-3 million prospect if he was in the draft as a pitcher-only. The bonus for where he'll likely be drafted $6-7 million.

When I saw Griffin make a start early this spring, I came away extremely impressed by his ability as a pitcher. That day, Griffin sat 93-95 and hit 97 mph, mixing in a slider that flashed above average potential, a usable changeup he didn't really need against high school hitters and shockingly good command for a prep pitcher throwing in the mid-90s.

Since the level of competition Griffin faces as a prep player is much more difficult to judge his ability against than a major conference college star like Caglianone, data-focused teams look at two key metrics to guide their decisions on high school position players: age and summer contact rate.

Griffin will still be 17 years old on draft day, among the youngest players in the draft, which elevates him in the eyes of some teams. His summer contact rate (performance in showcases or tournament games using wood bats against other top prospects) was also good, especially for a player some scouts had labeled as a tools-over-performance type. One team measured nearly 100 summer plate appearances from Griffin, with an OPS of almost exactly .800 and a strikeout rate of 17% with a walk rate of 10%.

While he didn't pitch more than an inning or two at a time last summer, Griffin did throw on TrackMan units and his Flaherty-like delivery and stuff held up to the data. His extension was well-above average, helping give him a flatter-than average approach angle to the plate, helping his fastball play well up in the zone, as it appeared to my eye, and that's how he uses the pitch in games. That's particularly impressive because it's something draft prospects and their coaches often don't understand or optimize. By definition, most pitchers also don't have an inherent advantage in this way. Griffin comes about it naturally, without focusing much on pitching. All the more reason for a team to believe he's just scratching the surface on the mound.

Griffin confirmed that this improvement on the mound this spring came from an increased focus on pitching.

"I probably spent 70-80% of my time training working on hitting and being a position player," he said. "It shifted to almost 50/50 in season because I was pitching a lot. I don't know how much I'll pitch at the next level, whether it's at LSU or pro ball."

The two-way bumpFor all the positives about both players, when teams are picking at the top of the draft, even little things in a scouting report can be the difference between a prospect being selected or sliding down a team's draft board. That's particularly true for players like Caglianone, an expected top-five pick, with the little things adding up to a $7 million-$9 million bet, given his expected signing bonus.

That's where two-way value really comes in. Imagine yourself in an MLB draft room on draft day. If you are the general manager or a scout pounding the table to make the bet on Caglianone as the player to take over the other, potentially more polished hitters at the top of the draft, you know that doing so comes with the risk that he never quite figures out his chase problems and the pick doesn't work out.

In that scenario, Caglianone's potential as a pitcher is viewed by teams more as a very intriguing backup plan if the bet on him as a hitter doesn't work out. Let's put it this way: If Caglianone was in this draft only as a pitcher, that second-round grade would likely net him a $1-2 million bonus. Knowing that option is available if his main thing doesn't work out will make anyone in the room pushing for him on draft day feel a little more comfortable. If a GM fails by picking a power hitter in the top 10 that busts, but ends up with a decent big league pitcher rather than a total bust, that may be seen as a consolation prize rather than a version of success. But that's not always how the psychology in a draft room works: Avoiding complete failure is alluring.

Griffin's path to the majors will take longer to come into focus due to his age, but his ability to both pitch and hit also indicates one of baseball's most desired qualities in this age: on-field athleticism.

Particularly in the last few years, teams are increasingly leaning into sports science-style testing to measure natural athletic ability and get a true picture of upside. In the same way NFL teams were focused on basic combine measures like the 40-yard dash or bench press, but then moved into functional on-field speed in pads, and agility or explosive measures, MLB clubs have also evolved.

Batting practice displays gave way to maximum exit velos about seven years ago, then to 90th percentile in-game exit velos, and now the cutting edge is a combination of in-game launch angle consistency, bat knob physics sensors like Blast Motion, or markerless motion capture video that maps the body and bat through the whole swing, often with the player standing on force plates in a gym setting. If you want to see an analyst's eyes light up, ask about Vertical Bat Angle (how far below the knob the bat head is when making contact with a middle-middle pitch) -- the hot new metric teams are using to quantify hitting ability in an effort to get an edge.

This approach has only been widespread for a few years, but there are teams that won't draft a player without force plate data. An exec for one of those teams described the output from the force plate testing as the "horsepower" for that player. It can be applied to first-step quickness on defense, to bat speed upside, to velocity upside on the mound. A few clubs excel at teasing out extra velocity from pitchers or power from hitters by scouting standout force plate performers, and now they compete with one another for these types of players in the draft to push that edge.

For Griffin, he already stands out for each of those things on the field, and his lofty force plate numbers -- "among the best in the draft class," a source said -- confirm what scouts are seeing, maybe even allowing them to round up on how those abilities will develop. But it's his ability on the mound that could be what separates him from other prospects in the same range, even to teams looking at him as a position player only in pro ball.

Front offices have come to realize that two-way performance is an indicator of overall athletic ability -- the same way some teams value multisport athletes -- because, in short, every time Griffin hits 98 mph on the corner with a delivery that suggests he'll keep doing it, he is showing the same functional explosiveness they are prioritizing in a hitter.

What happens at decision timeIt's easy to imagine either of these players improving once he only has to focus on one aspect. So that's where the next big dilemma comes in: Deciding when to let go of the two-way dream is a difficult dilemma.

To account for this, we've seen a number of teams have high-profile prospects do the thing they are best at most of the time, while also letting them dabble in the other. Masyn Winn threw one inning in pro ball in 2021 as St. Louis kept the idea of pitching alive early in his pro career before he ascended to the majors as a shortstop. Pittsburgh Pirates prospect Bubba Chandler racked up 188 plate appearances in pro ball in his first three pro seasons before focusing fully on pitching. The Rays developed two-way collegiate star Brendan McKay both ways, thinking he'd be a position player, then realizing about a year later that they were wrong, before injuries derailed his pitching career.

Sometimes, teams will use instructional leagues for experimentation on the lesser-regarded skill to see if it's worth continuing. For example, after being announced as a two-way player when the San Francisco Giants took him in the first round of the 2022 MLB draft, Reggie Crawford's pro hitting career likely ended after a .138 average in the Arizona Fall League, as harnessing his 100-mph fastball and late-inning potential has become the focus.

I spoke with an exec who summed up that type of tough decision: "It'll get to a point where you know the player is better at one thing than the other. So when it's clear that playing both ways is holding back the better thing from improving, then you have to pull the plug."

How this will play out for Caglianone and Griffin could come down to which teams call their names on draft day. Scouts and execs perceive the approach of keeping the lesser ability alive for a year or two as something more progressive, analytical teams do it for risk mitigation, while old-school, scouting-oriented teams tend to want a player to focus on whichever area they think he's even just a little better at. Though in the case of high-profile two-way talents, a team might let the player do both even against their own internal evaluations, sometimes as a consideration to keep the player happy in the short-term, rather than simply closing the door without attempting to make it work.

Caglianone and Griffin might not end up being the next Ohtani, but their two-way prowess is impressive -- and gives them a major leg up on the competition as the 2024 MLB Draft approaches.